Are Climate Models Too Coarse?

Or do they have a different problem—and why that matters for the preservation of the biosphere.

The New Year 2026 has just started, but as usual its first month is already over. Here is a brief closing post for this January (to make it three per month, as I promised myself), though it is more of an announcement of another topic that I hope to develop in the near future.

In brief, what I want to say is that many people tend to think climate models err because they lack sufficient resolution — that they are simply too coarse. I discuss some arguments, rarely presented to the public but well-known to professionals, indicating that increasing resolution in current models does not actually lead to expected improvements. My own perspective is that this is because the models lack a proper constraint on their behavior. This constraint lies in the relationship between condensation rate and wind power in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Neglecting this constraint, and tuning models as if differential warming were the only thing capable of driving air motion, can lead to incorrect and strategically dangerous conclusions that forests do not matter for the terrestrial water cycle.

For some readers, this could be another dense post. But this is what concerns me very deeply, so from time to time I have to let these thoughts out.

Recent problems with climate models

You can’t easily prevent people from thinking and trying to form their own independent opinions. For example, in a recent Nate Hagens’ podcast, materials expert and investor Craig Tindale noted:

I got bored in Covid, so I decided I’d read the IPCC climate models and then I went down rabbit holes in all parts of the climate models. I’m far from an expert because I don’t hold any any degrees in it. But I certainly understand the models. The models were extraordinarily wrong. You know, I position it as the skeptics and the climate activists were both wrong. You know, they’re talking about 2100 and things that are going to happen out there. What they missed was their models were too coarse and the fact the whole thing is accelerated much faster than we thought that it would and so they were wrong as well. And so our window to change is is basically closed. …

you’ll get people like James Hansen and Leon Simmons who have put extraordinarily blunt research out there recently saying does everyone know this is accelerating faster than we thought.

Indeed, our climate projections—the ones society has an opportunity to discuss—are derived from global climate models. These are sophisticated programs that solve the equations of hydrodynamics on a grid with finite resolution. Recently, society has learned that models do not correctly depict some of the changes that are underway. Many of these changes are, in fact, happening faster than predicted (see my discussion of hot models in “On the scientific essence of Dr. James Hansen’s recent appeal”).

This idea—that models should simply increase their resolution in order to become more and more reliable—is very much in line with the thinking of specialists engaged in incremental science. The path is chosen; all that is needed is to move forward. And more resources. However, some people can see indications that this could be a path to nowhere.

I am not a modeler myself; I am more of an advanced consumer of model outputs, which I analyze as a theorist, drawing on observational data and my own understanding of the Earth’s system. So let me explain what I mean.

Too coarse to fail

The problem is that the external constraint we know for the climate system is the differential distribution of absorbed solar radiation. Warm air rises, cold air descends, all that. In principle, atmospheric motions should be reproducible from this information together with what we know about the planetary surface. In practice, however, because there is no theory of turbulence (which can be understood as friction destroying wind kinetic energy), this friction must be tuned so that simulated winds match observations.

Take the Hadley cells as an example: air rises at the equator, where solar input is strongest, and descends near 30° latitude. Friction coefficients are tuned so that near-surface meridional (north–south) velocities are about 2 meters per second. They are not derived from first principles, they are tuned to observations.

This scheme shows a model grid (squares) and the resolved large-scale air motion across the grids.

But once this tuning produces realistic winds, another problem emerges: precipitation is wrong. The rainfall patterns generated by those winds do not agree with observations.

For a long time, this was blamed on coarse model resolution. Precipitation involves air rising through roughly ten kilometers of the atmosphere, while early model grid spacing was much larger—often 100 km or more.

To cope with the unrealistic precipitation, an additional tuning was introduced within each grid cell, called convective parameterization (on convective parameterization, see also “The tug-of-war between forests and oceans”.

This allows rainfall and latent heat release to occur relatively independently of the resolved large-scale flow, as if air were rising and descending entirely within a grid cell.

This scheme shows the large-scale (resolved) air circulation, and parameterized convective motion within columns.

This naturally added substantial arbitrariness to the models.

But the hope was that as horizontal resolution improved and grid size dropped below about 10 km, convective parameterization could be abandoned. Precipitation would then be generated by resolved motions alone, leaving turbulence as the only process requiring tuning.

That hope was not realized. Even in very high-resolution models, convective parameterization remains necessary; without it, rainfall is unrealistic. Below I quote an excerpt from the discussion following a very interesting lecture by Dr. Vidale on high-resolution model development. While the lecture showcased many successes, the Q&A revealed many problems (emphasis mine).

From the audience: Hi thanks a lot for the very inspiring talk it’s XXX from Meteo Swiss and in the global NWP [NWP – numerical weather predictions -- AM] it seems that going from 10 kilometer towards five or two kilometer we don’t have a straightforward improvement of this course and maybe it’s because of parameterizations are not ideal for these scales or we don’t know which one to switch off and the question is whether we should jump to even higher resolution to get around this so-called disgrace and how do you would say this is for climate application and projection?

P.L. Vidale: Funny you should say that we spent a year and a half debating this in Erie and nobody could agree and in the end we decided not to say anything about it and we’re very lucky that Christoph was not one of the reviewers otherwise we would have been in serious trouble.

Somehow the reviewers sort of missed it but I have to say that the feelings around this issue are very strong and there is one group that absolutely believes we should switch off convective parameterization no matter the scale and there is another group that believes we need to keep it on.

So Friday we were looking at next-gen results and I can tell you that the four kilometers in the IFS if we disable even the deep convective parameterization we have a huge error over the ITCZ [Intertropical Convergence Zone — AM] and this is three times the precip[itation] that we should have over the ITCZ and the other issue I don’t have time to show but there’s a lot of popcorn all over

so in the end even at four kilometers we had to enable shallow and deep [convective parameterization — AM] in the IFS otherwise just wrong so this is a huge issue and yes maybe we need to go all the way to one or 220 meters like our Japanese colleagues are doing but currently we don’t have such capability I would say mostly on the side of software we have the compute… Bjorn is saying now we have far too much computing what we don’t have is the capability and I tend to agree with that

but also to jump all the way to one kilometer without knowing about all the other parameterizations like um what’s happening with with um turbulence so we were seeing again developments of the Smagorinsky scheme in nikam and and they’re doing a lot of work around that so so it’s it’s not just about increasing the resolution blindly we need to do a lot of work around these things and I really do believe here that the regional models can help and we should work together.

What they conference participants are essentially discussing is that after tuning turbulence to produce the correct horizontal winds under the observed differential heating, rainfall is still not generated correctly. Even though the horizontal resolution is now much smaller than the height of the atmosphere, they nevertheless have to switch on separate “tricks” (convective parameterization) to produce realistic rainfall within each grid cell.

What is the problem?

Of course, one could try to go further by increasing the resolution, but from my perspective the problem is probably conceptual. Turbulence and precipitation are related, and if this link is not included in their representation in models, one will always have to tune them separately.

The problem is that differential heating is not the only process that generates pressure gradients and drives winds in the Earth’s atmosphere. As we discussed in our previous post on hurricanes, precipitation—which differentially removes gas from regions of low pressure—also generates pressure gradients that can drive very appreciable winds. In fact, as Heinrich Hertz thought, and as we agree, this mechanism may be more significant than differential heating.

The atmospheric engine generates wind power that is related to condensation. Friction dissipates this wind power. Therefore, condensation and frictional dissipation are tightly linked.

There is quantitative theoretical argumentation showing how much wind power can be derived from observed precipitation, and it agrees with observations. However, as one thoughtful reader recently commented, taking this into account would require a gargantuan rethinking of how the atmosphere works. The stability of existing understanding and incremental progress are currently being preferred over conceptual disruption (which we are hoping to evoke anyway).

It is not innocent

Readers often politely imply in their comments: what on Earth does all this physics—hurricanes, precipitation, turbulence—mean for our understanding of the water cycle on land, and for how to keep land habitable and thriving? Setting these matters straight is very important.

If a model is tuned to generate winds only in response to differential heating, it may conclude—along the lines of a recent study discussed in our recent work—that the Amazon forest could be destroyed (and trees removed more generally) without any danger to the terrestrial water cycle. The idea is that without evapotranspiration the land becomes warmer, the contrast between land and ocean increases, and stronger winds should follow. (Yet the Amazon forest is cooler than the ocean and still drives winds inland.)

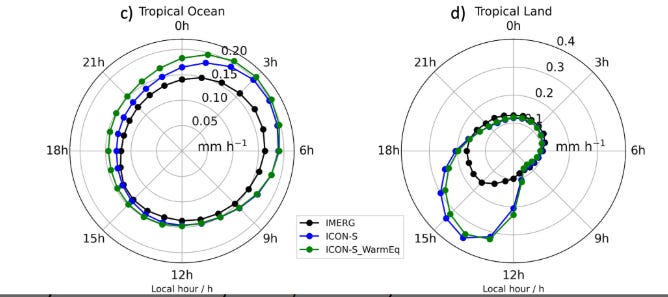

The mismatch between observations and models in how precipitation is reproduced is not a minor issue but may represent the visible the tip of an iceberg hidden in model structure: the missing link between condensation and wind power. For example, high-resolution models struggle to reproduce the diurnal precipitation cycle over tropical land areas:

Fig. 1 from Segura et al. 2022. Shown is the diurnal cycle of precipitation in observations (IMERG) and high-resolution models.

One can see that the modeled peak, which is much higher than observed, occurs closer to midday, while the observed peak happens later in the afternoon. This may seem like a minor issue—after all, the model reproduces many other atmospheric parameters, like wind speeds, satisfactorily. But this discrepancy suggests that the model generates ascending air motion mainly from direct thermal forcing, with maximum solar input at midday. The dynamic feedbacks between cooling, condensation, and convection are not properly worked out. Thus, this seemingly minor mismatch indicates that the model may not be adequate for describing forest-mediated moisture transport. Nor can it govern our large-scale forest policies.

If our civilization is indeed heading toward a near-term decline, this may be the last moment when we still have an enormous abundance of data to understand, in quantitative terms, how profoundly the biosphere matters for Earth’s habitability. We may lose these global datasets sooner than we expect.

If we do this work now, and acquire the new understanding, we can carry this quantitative science forward and memetize it for future generations in an accessible, scientific, and rational form. In this way, preserving the biosphere would rest not only on spiritual knowledge inherited from the past, but also on clear scientific argumentation—even if future generations no longer have the capacity to collect environmental data at today’s scale.

So long live the biosphere, and we continue our work.

I was going to say that this was another case of GIGO - Garbage In = Garbage Out, but in fact our Data In might be wonderfully precise, accurate and at a very fine resolution, but if the equations handling that data are inadequate or incomplete, we will continue to get GO, whatever the resolution. I suppose we have to get a modeller on board (Ali from Regenesis says he can model some influence of trees) and derive a model with better, more complete equations, and then run that against the data we have. If we can produce a model with the Biotic Pump fully described by the included equations, and this model produces much better accuracy (between prediction and actual data) even at 10km horizontal and 1km vertical resolution, then we will have shown that the problem is not the resolution, but the weather system we are trying to describe with our equations.

Anastassia, much appreciation for the work on bioregulation. In a sense it was proven already as a major component of temperature decline in Western Europe during the Little Ice Age:

https://phys.org/news/2011-10-team-european-ice-age-due.html

It's unlikely climate models can be developed fast enough to incorporate the feedbacks mentioned here: https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/feedbacks.html

Many of them are positive and visible on satellite maps already:

https://climatereanalyzer.org/wx/todays-weather/?var_id=ws250-mslp&ortho=1&wt=1

The Arctic jet stream at January 31 is over Texas and South of the Russian Federation, the Antarctic jet stream is fragmented.

The temperature maps on the site indicate fast melting of polar ice. Have you (and team) modeled what would happen when reforesting deserts like Atacama and Sahara?