Science Insider #2: Working Our Path Forward Through Rain and Hurricane Wind

Hurricanes can serve as toy models for understanding how forests can move atmospheric water. The precipitation mass sink is underexplored—why is its scientific discussion discouraged?

With the world in turbulence, today’s post turns to hurricanes. It’s dense, and it picks up a complicated thread from Part #1. First, we look at how rain contributes to hurricane intensification—genuinely exciting stuff. Second, we dig into the intrigue, controversy, and complexity of an ongoing debate unfolding in the Journal of Atmospheric Sciences of the American Meteorological Society. Finally, I reflect on my own reactions to all this.

Rain and Hurricane Intensification

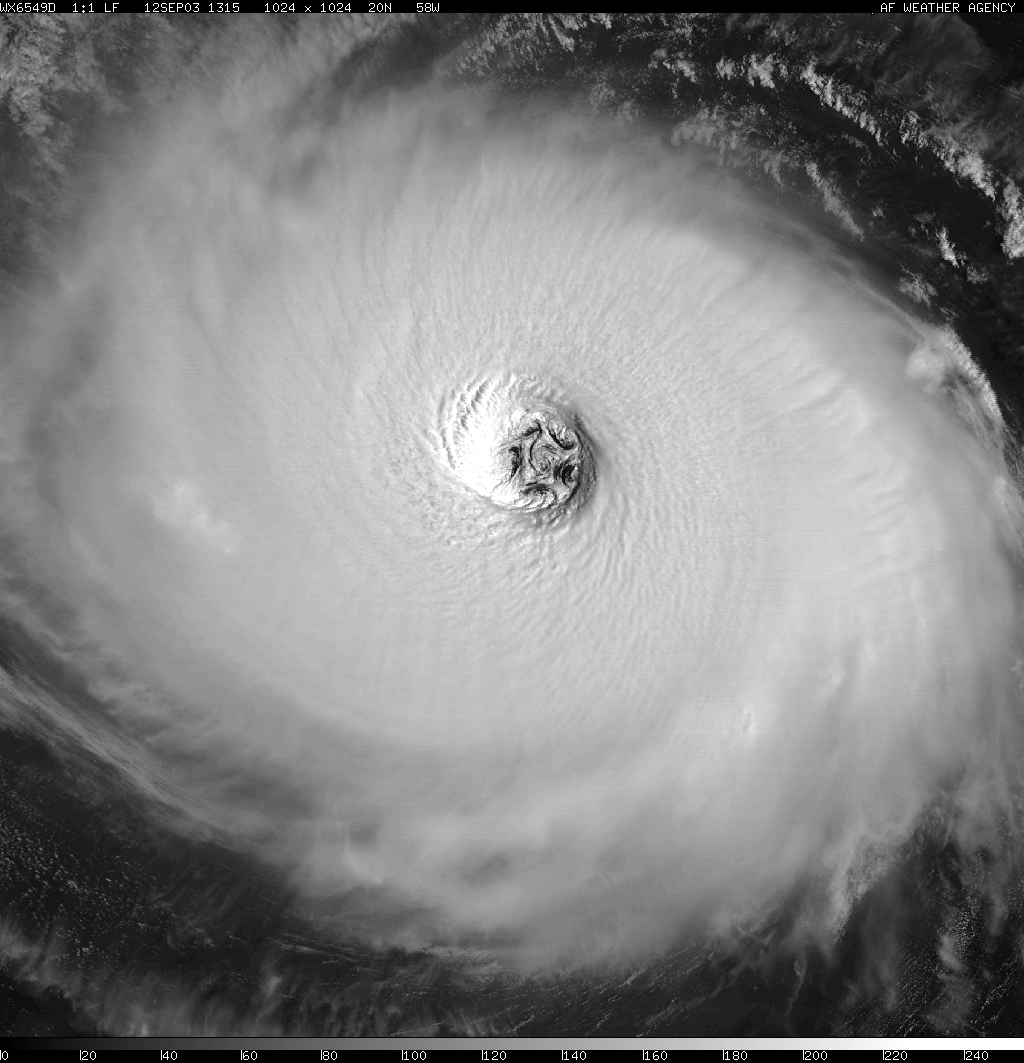

When we look at a hurricane from space, we see a vast, nearly circular system of bright clouds. What remains hidden is what lies beneath them: a deep region of low atmospheric pressure that decreases toward the storm’s center. This pressure difference draws air inward from all directions.

Because Earth is rotating, the inflowing air cannot move straight toward the center. Instead, it curves and begins to rotate. As the air approaches the core of the storm, its rotation speeds up—much like a figure skater who spins faster as she pulls her arms inward.

Surface air pressure is simply the weight of the atmospheric column above us, roughly equivalent to the weight of a ten-meter column of water. From this perspective, the pressure minimum can be pictured as a pit with less air than its surroundings. Hurricane intensification can then be understood as the formation and deepening of this pressure well.

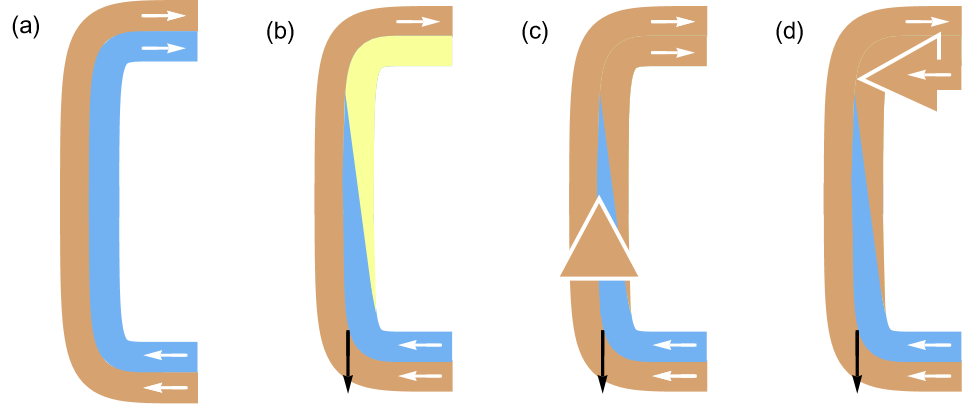

The cylinder represents the atmosphere, the deepening pit represents the area of decreasing pressure from which air is removed.

How quickly this pressure well forms in real storms can be estimated directly from observations. For Atlantic tropical storms, the Extended Best Track dataset provides storm positions and central pressures at six-hour intervals for every recorded system. Averaged across all storms, the median rate of central pressure fall is about 12 millibars per day. Much faster deepening does occur, but it is rare. In meteorology, rapid intensification was defined as a pressure fall exceeding 42 millibars per day. In the most severe storms, the central pressure can ultimately drop by 100 millibars or more, reducing normal air pressure by more than one tenth.

This brings us to the central question: what sets the rate of this pressure fall? Why is it typically on the order of ten millibars per day, rather than one hundred millibars per hour—or, at the other extreme, only ten millibars per week?

Lowering the air pressure in the hurricane core requires removing mass from the atmospheric column. The problem therefore becomes one of accounting: which processes add mass to the column, and which remove it?

Broadly speaking, there are three such processes. First, moist air flows into the storm at low levels (the horizontal blue arrow). This air then rises (not shown), dries as it loses moisture through precipitation, and exits the storm in the upper atmosphere (the horizontal brown arrow). In addition to this horizontal circulation, precipitation removes condensed water directly from the atmospheric column (the thin vertical arrow).

Which of these processes actually controls how fast the pressure well deepens? Observations show that the inflow and outflow transport several hundred times more mass into and out of an inner region—say, within 100 kilometers of the center—than is removed by precipitation falling as rain. There is a very large inflow, a very large outflow, and a comparatively tiny direct loss of mass by precipitation. Given this imbalance, what outcome should we expect?

If you pause to think about it, this is not a trivial question.

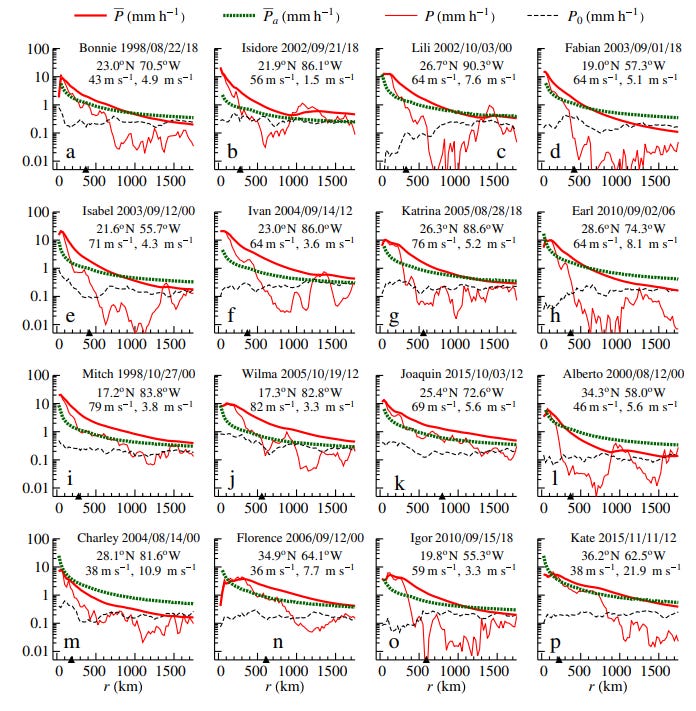

Now imagine our reaction when we carried out the analysis. This required matching precipitation data to all hurricane positions and computing the radial distribution of rainfall for every storm.

Examples of radial precipitation distributions for several major Atlantic hurricanes from our earlier work. Thin red curve indicates local rainfall at a given radius, thick red curve indicates mean precipitation within that radius, black dashed curve indicates climatological precipitation in the same region without a hurricane, for other notations please consult the original publication. Note the logarithmic scale on the vertical axis.

What we found was striking: in the storm core—the region of maximum precipitation—the precipitation rate closely matches the pressure deepening rate, about 14 mb/day versus 12 mb/day. (To express precipitation in mb/day, one multiplies the mass removed per day by gravity, g.) To our knowledge, no such analysis had been done before.

The result was remarkable. If I could speak with Victor for just a few minutes, and he asked how I had been, I would not tell him about COVID or wars, but about this finding. When he passed away in May 2019, one of his unfinished papers concerned storm intensification; we now see that the intensification rate of hurricanes practically coincides with the concurrent precipitation rate in their core. When we began our work on the biotic pump physics to show that the dynamics of the condensation sink is a major driver of atmospheric circulation, we did not know this.

Intrigue

Since there is no generally accepted theory of storm intensification, and many discussions are ongoing, submitting our work for evaluation was, naturally, a moment of suspense. We first published a preprint and then submitted the manuscript to the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, a journal of the American Meteorological Society. JAS does not have a particularly high citation index, but it hardly needs one: it is a well-established venue for a relatively small, elite community of atmospheric theorists to present and debate serious work.

The evaluations from three reviewers, received a few months after submission, were positive and constructive—a very pleasant surprise. To quote from the opening lines of the reviews (with my emphasis):

Reviewer 1: It's an interesting study that links tropical cyclone intensification rate to mass removal from the air column (precipitation). Our focus of how moist process impacts intensification is often on diabatic heating while this manuscript gives another seemingly important process - precipitation fall-out. It explains partially why a reversible tropical cyclone cannot intensify as fast as a pseudoadiabatic tropical cyclone. I like the content of the manuscript which discusses a lot of interesting and novel ideas. But the current version does not give a clear explanation of the mentioned processes. I would recommend a major revision.

Reviewer 2: The role of the condensation mass sink in tropical cyclone (TC) intensification is examined using both observations and idealized numerical model simulations. The main finding is that the condensation mass sink is an important process in TC intensification, perhaps more important than other previous studies (Lackmann and Yablonski, Bryan and Rotunno) have shown. The study contains interesting new work on the condensation mass sink's role in TC intensification. It could be publishable subject to addressing a few major and minor issues, which are noted below.

Reviewer 3: In this study, the authors examine the relation between tropical cyclone (TC) intensification rate and maximum rainfall rate, using observational analyses of TCs in the North Atlantic and CM1 model simulations. Their main conclusions are 1) the lifetime maximum intensification rate of a TC is caused by the condensation mass sink related to precipitation falling out of the TC system, and 2) condensation mass sink is a part of a positive feedback mechanism between the TC central pressure and vertical motion in TC development.

Overall, this is interesting research, addressing an open question about the impacts of mass sink related to condensation mass sink in TC development that is worth considering for publication. I do have however two main concerns that I would like to hear from the authors, and so would recommend a major revision such that the authors could have a chance to reply and/or justify their results.

All three reviewers recommended a major revision, which was expected: the ideas were new, and many points required clarification. However, the editor rejected the manuscript, contrary to those recommendations. The main argument was that our theory implies that, once a tropical storm reaches a steady state, its precipitation must vanish—since there is no further intensification. Observations, by contrast, indicate that storms tend to produce their most intense rainfall near the time of maximum intensity. This was a misinterpretation of our work, to which we return below.

What we took from this disagreement between the reviewers’ assessments and the editor’s decision was that the situation was sociologically complicated. Handling editors bear full responsibility for publication decisions, and they may consult colleagues beyond the formal reviewers—who remain invisible to the authors but whose opinions can carry significant weight. At the same time, the scientific picture was itself confused, shaped by earlier work that had concluded that the vapor sink plays no significant role (as mentioned by Reviewer 2).

Therefore, rather than immediately throwing our intellectual child back into those turbulent waters through a revision and re-submission, we decided first to feel our way toward firmer ground and set the record straight on one essential point: to establish, beyond reasonable doubt, that the precipitation mass sink is a significant term in the mass budget of any tropical storm. To this end, as explained in Part #1, we wrote a short commentary on a recent paper that attempted to construct a theory of storm intensification while neglecting the precipitation mass sink altogether. Since the AMS normally encourages such discussions, this provided a good opportunity to convey the message succinctly—while also correcting an unjustified violation of mass conservation along the way.

Our commentary was evaluated by a single reviewer, who agreed that the criticism itself was valid, but nevertheless recommended rejection because the authors of the criticized paper—after some hesitation—declined to provide a response. In the reviewer’s assessment, the absence of such a response rendered the criticism “without context,” even though that absence resulted from the authors’ own refusal to engage. The same editor who had handled our first paper made the decision to reject the commentary.

We therefore provided the necessary context ourselves and resubmitted the commentary; this is where Part #1 ended.

Controversy

Recently, we received a response from the journal rejecting our commentary once again, this time after evaluation by two reviewers. The editor noted that these were new reviewers; the earlier reviewer who had judged our criticism to be valid was not involved.

A complete exchange with the reviewers and the editors can be found in Appendix A of our updated preprint. From one of the reviews (my emphasis):

The authors of this Comment raise an important and potentially valid critique regarding the physical basis of the S&T [Sparks and Toumi — AM] (2022) model. Their argument—that the precipitation mass sink is a critical component of the surface pressure tendency in tropical cyclones—is at least intuitive and may be correct, though the role of mass removal due to precipitation remains largely unexplored in the broader community (this does not necessarily diminish its potential importance).

At this point, the discussion develops two distinct but related foci. The first concerns whether our criticism of the work of Sparks and Toumi (2022)—in which precipitation was omitted from the storm mass budget—is valid. The second concerns whether storm intensification is, in fact, controlled by precipitation.

With respect to the first question, one of the two reviewers raised an important point, echoing earlier concerns expressed by the handling editor. He argued that the storm’s mass budget can be decomposed into two components by considering dry air and water vapor separately. Since the total amount of water vapor within the storm is small and changes very little during storm development, nearly all of the water vapor entering the storm must be removed by precipitation, without affecting the total mass budget. Under this interpretation, changes in central pressure are determined solely by the difference between the inflow and outflow of dry air.

Schematic representation of the argument raised by the reviewer. The low-level inflow is separated into dry air (inward brown arrow) and water vapor (blue arrow). All incoming water vapor is removed by precipitation (vertical blue arrow), while the dry air exits the storm in the upper atmosphere (outward brown arrow). Under this interpretation, changes in total mass—and thus in central pressure—are determined solely by the difference between the inflow and outflow of dry air. Where, then, does precipitation enter the control of storm intensification?

The reviewer’s point, as applied to the work of Sparks and Toumi (2022), was essentially this: if their model is to work while ignoring the precipitation term, then the pressure tendency should have been written explicitly in terms of the inflow and outflow of dry air, not total air, as they actually did. The reviewer stressed that Sparks and Toumi never made this distinction, and that this should be stated clearly.

To cut a long story short—and to get back to the more interesting questions—below is the letter to the editors that we sent with our latest resubmission of the Commentary.

Date: 28 January 2026

To:

Dr. Daniel Stern, Handling Editor

Dr. Zhuo Wang, Editor in Chief

Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences

Subject: Editorial action regarding Sparks and Toumi (2022)Dear Dr. Stern and Dr. Wang,

We write concerning our Comment on Sparks and Toumi (2022), which identifies an unjustified omission of the precipitation term from the pressure-tendency equation. We are grateful to the reviewers for their careful evaluation.

One reviewer stated explicitly that the criticism is valid. A second reviewer characterized it as potentially valid but did not address its substance, instead suggesting development of a standalone paper with a new theory. A third reviewer noted that the model of Sparks and Toumi (2022) would be valid if total air density were replaced by dry-air density, acknowledging that this should be noted. Importantly, none of the reviewers refuted our central claim that, as currently formulated, the model is not valid.

While we respect the editorial decision, we are concerned that the present outcome [i.e., with our commentary rejected — AM] leaves an acknowledged inconsistency unaddressed. In its published form, the model does not specify dry-air density in the governing equations.

Although total air density and dry-air density differ by only about one percent, the key diagnostic quantity—the column-mean velocity—can differ by more than 100% and even change sign depending on which density is used. This is therefore not a minor issue. Moreover, while the equations could in principle be reinterpreted, the numerical analyses cannot be retroactively corrected: they necessarily used either total air density or dry-air density, and this choice must be made explicit.

In our view, if total air density was used, publication of our Comment would be the appropriate mechanism to clarify the issue for readers. If dry-air density was used, a corrigendum would be required. In either case, leaving the matter unresolved does not seem consistent with AMS standards of scientific rigor and self-correction.

We therefore respectfully ask that the journal either reconsider publication of our revised Comment, which addresses all reviewer comments, or request that the authors of Sparks and Toumi (2022) publish a corrigendum clarifying the formulation.

Thank you for your time and consideration. We look forward to your response.

Yours sincerely,

Anastassia Makarieva

This letter also had a sociological calculation behind it. If the authors of Sparks and Toumi (2022) were to refuse to publish a corrigendum—much as they had earlier declined to engage with our criticism (see Part #1)—that refusal could itself strengthen the case for publishing our commentary. Publishing a corrigendum, on the other hand, would in any case require acknowledging our work.

If the journal were instead to decide on no action at all, then, given the visibility of the issue—a clear violation of mass conservation—we would have the option of respectfully appealing at a higher level within the AMS, simply to see where this resistance to the precipitation mass sink ultimately ends.

In any case, the more researchers are drawn into this controversy, the more it encourages independent thinking about the currently neglected dynamics of the precipitation mass sink.

Complexity

Let us now turn to the core of the physical argument raised by the reviewer: that the mass—and therefore pressure—change in the storm core is determined entirely by the inflow and outflow of dry air.

At first glance, this looks like a decisive argument, one that should end the discussion leaving no role for precipitation in storm intensification. The editor indeed described it as critical, and it formed the basis of the rejection.

There is, however, a stubborn counter-argument supplied by the storms themselves: observations show that precipitation rates and intensification rates practically coincide.

As a concrete, real-world example, Hurricane Milton (2024) underwent rapid intensification, with its central pressure falling by 84 mbar in just one day. For such a pressure drop to be sustained by precipitation alone would require rainfall rates in excess of about 35 mm per hour—equivalent to removing roughly 840 kg of water per square meter per day.

And that is exactly what was observed. Reconnaissance flights into Milton recorded peak local precipitation rates exceeding 33 mm per hour, with maxima reaching well above 60 mm per hour.

The numbers are not merely consistent; they are uncomfortably close. How can this be reconciled with the argument above?

In fact, we had already explained this in the very first submission of our commentary. The reviewer at the time judged that this material was not directly relevant to our critique of Sparks and Toumi (and, strictly speaking, it was not), so we removed it in the revised submission. As a result, unlike the editor, the new reviewers never had the opportunity to evaluate it.

Let us therefore revisit this line of reasoning, beginning with a simple thought experiment.

We start with a deliberately artificial case. Imagine that water vapor does not condense when moist air rises, but instead behaves as a passive tracer carried along by the flow. We assume a steady-state circulation: whatever flows into the storm also flows out, and the air pressure does not change. This idealized situation is shown in panel (a).

Dry air and water vapor are shown in brown and blue, respectively. Thin white arrows indicate inflow into and outflow from the atmospheric column. Black arrows denote the outflow of condensate (precipitation). Large triangles indicate the direction of pressure adjustment, that is, the direction of air motion required to fill a pressure deficit. Yellow shading marks the pressure deficit that appears upon water vapor condensation.

Now let us allow the water vapor to condense as it rises, with the condensate removed by precipitation, shown by the black arrow in panel (b). At the same time, we deliberately hold the flow velocities fixed. In this imagined case, the circulation remains steady: less water vapor leaves the column in gaseous form, but that reduction in gaseous outflow is exactly balanced by removal through precipitation. Panel (b) thus represents the situation implied by the reviewer’s argument. In this picture, precipitation by itself does not lead to intensification; it merely provides an alternative pathway for the condensed vapor to leave the column. As in panel (a), panel (b) also contains two inward and two outward arrows.

However, if precipitation were to occur without any adjustment of the flow, the result would be a strongly non-hydrostatic column, with an uncompensated vertical pressure difference Δp of the order of the water-vapor partial pressure, Δp ≈ pᵥ ≈ 30 mb. If such a pressure imbalance were to persist (as indicated by the yellow shading in panel (b)), it would drive vertical velocities in excess of 50 m s⁻¹, which are clearly not observed in tropical storms.

This immediately tells us that precipitation must be accompanied by pressure adjustments. If that adjustment occurs primarily in the vertical, the pressure deficit aloft is compensated and the outflow is restored, up to—at most—its unperturbed value. Once inflow and outflow again balance, the surface pressure begins to fall, now at a rate equal (in the maximal case) to the precipitation rate itself. This is the case shown in panel (c): precipitation does not change the mass budget by itself, but it forces the flow adjustment that does.

To make this less abstract, here is a short video that illustrates what a vertical pressure adjustment of this kind can look like. The bottle initially contains hot water vapor. As the vapor cools and condenses, a pressure deficit forms, and fluid from below rushes upward to fill it.

In other words, precipitation not only removes the incoming water vapor, but also creates a deficit of air pressure aloft that, as shown in panel (c), can drive an additional upward and outward flow of dry air.

It is hard not to find this conclusion a little mind-blowing.

But there is more. Under different circumstances, and with a different flow geometry, the pressure adjustment can occur aloft in the horizontal direction, as shown in panel (d). In that case, the adjustment reduces the outflow, rather than increasing it as before. As a result, the storm weakens—again at a rate determined by precipitation.

A horizontal adjustment is easy to imagine. Suppose we do not allow the condensate to fall out, but instead keep it suspended in the air as tiny cloud particles. These particles still contribute their weight to the atmospheric column, so a vertical pressure adjustment is no longer possible. Horizontally, however, the situation is different: liquid water now occupies space previously filled by gas, creating a pressure deficit into which the surrounding air will flow in order to restore balance. From this, we would expect storms in which condensate is prevented from falling out to intensify only very slowly, if at all. This is exactly what is found in model experiments (more details can be found in our work in arxiv, see, in particular, Table 1 and Figures 6 and 10).

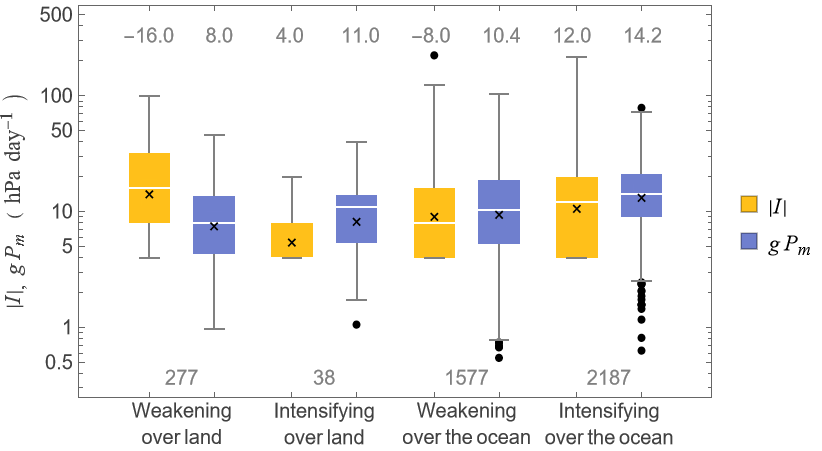

Moreover, the reasoning illustrated in panel (d) suggests that weakening rates in tropical storms could also be set by precipitation. In agreement with this expectation, de-intensification rates in tropical storms are also close to precipitation rates

Intensification rates I and precipitation rates gPm, in mb/day, in weakening and intensifying Atlantic storms (Fig. 1 from Makarieva and Nefiodov https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.14717v3 )

Finally, it is easy to imagine intermediate flow geometries in which vertical and horizontal pressure adjustments partially compensate each other, producing a steady-state storm. This can resolve the editor’s concern discussed in the Intrigue section of this post, based on the assumption that our approach would imply zero precipitation in steady-state storms simply because their intensification rates vanish. In our framework, steady intensity does not require zero precipitation—only a balance between competing adjustments.

Human Dimension

I find this physics absolutely exciting, and I am utterly happy to be working on problems like this. But people sometimes ask why the biotic pump has been slow to gain acceptance. As this story illustrates, every exchange, every small step forward—even when the ideas are admittedly novel and intriguing to open-minded observers—has to push its way through an enormous amount of resistance, only part of which, at least from my perspective, is grounded in rational scientific disagreement.

Perhaps the difficulty lies precisely there. As one of the reviewers noted, the ideas involved are novel—and there are many of them. That alone means they require a comprehensive assessment. When parts of the argument are set aside, whether deliberately or not, the remaining picture can easily appear illogical, or even fantasmagoric: in this case, how can precipitation possibly drive the pressure tendency of dry air?

I must admit that I have a tendency to dramatize things. When someone says that my work is not good, I feel it very strongly—often in a theatrical way.

But with some distance, I find that I can hold distinct perspectives at the same time. One is a sincere appreciation for the time and effort that members of the scientific community invest in evaluating our work, even when those evaluations are very critical. Critical feedback, when you eventually realize that it stems from a misunderstanding rather than from a real flaw, is extremely valuable. Each unsuccessful attempt to find a flaw only strengthens the robustness of the result.

There is also a deep sense of belonging in this process. It is a true pleasure to engage with people who share your sense of what matters in the world. They may be critical, but they will not say that questions such as how fast storms intensify are irrelevant. They understand that it matters—a great deal.

And yet, alongside this positivity, my thinking often swings in the opposite direction.

On Nate Hagens’ podcast, the psychoanalyst Nancy McWilliams made an observation about how therapists in different countries describe what they see as characteristic psychological tendencies in their own societies. She noted that Russians often describe themselves as masochistic, Italians as hysterical, and Swedes as schizoid. (An interesting discussion about Americans followed.)

At first, I thought that “masochistic” sounded too simple. In my own perception, Russians seem to live with an inner gaze constantly fixed on the precipice between life and death. Perhaps this has something to do with the vastness of the country, or with its harsh climate, but this underlying spiritual posture appears to blur certain boundaries. It may encourage behaviors that, in other cultures, would be firmly restrained by the instinct of self-preservation.

But then, when I think back on years of criticism—sometimes constructive, sometimes unfair, sometimes simply demagogic—I begin to wonder whether masochism is, in fact, part of the story. Perhaps one really does need a masochistic streak to survive it all: to outlive the criticism, to keep going, and still do meaningful work—and to enjoy the drama.

On the day we submitted our “vapor sink” paper to JAS, back in 2024, a very remarkable thing happened. A large hawk came to our balcony—in a very urban city, St. Petersburg—and gave us the pleasure of observing it for several hours. (Just how often do hawks visit urban balconies?) It felt almost magical, having completed important work, to watch this elegant bird of prey meditating on our balcony. I took it as a good sign: that our work could fly far and be able to defend itself. Let’s see.

Hello Anastassia, Another incredible post, part of which goes over my head, but it does elucidate the difficulty of getting new science accepted. Here is a pet theory I had a couple years ago, but I didn't have anyone to check it with. Is there merit in this idea, or should I discard it?

Hurricanes and typhoons as one of Earth’s cooling mechanisms.

My understanding is that one of planet Earth’s biggest cooling mechanisms is precipitation. Precipitation causes a big release of energy into the atmosphere (the energy it took to evaporate it or transpire it). Much of this heat is radiated out to space, cooling the planet. Hurricanes and typhoon dump huge amounts of rain. Thus they must release huge amounts of heat which radiates off planet. If so, we could consider big storms and torrential rains as methods the Earth has for cooling herself. I am sure there are science mechanisms at work here, but this is a simple way to put it. Until humans start regreening the Earth to cool the Earth, Nature may continue to scale up big storms.

Like many of your readers, I am still trying to get my head around the physics of hurricanes! However, two (simple) questions: (1) What would be the likely condensation nuclei in your sucking bottle experiment? I have been lead to believe that water vapor cannot condense without a nucleus, so what would have been the nuclei in your bottle? (2) You state (fairly early on) that "Surface air pressure is simply the weight of the atmospheric column above us" - is that not true only for still air? Would not some of the falling pressure you describe also be due to the Bernoulli effect of fast moving air having a lower pressure? I am sorry that I do not have time to calculate how much this might be, in relation to the pressure changes you describe - but then you could "run the numbers" in seconds, whereas it would take me a couple of hours to refresh my memory and get all the units correct etc. etc. I also need to try to understand that, if you are correct, that precipitation is an important cause of these pressure losses, then what relevance does that have for the Small (or Terrestrial) Water Cycle?